Interview: Rat Scabies

How The Damned Drummer Got Into Punk Rock

This is the final installment in a five part series about drummers and drumming.

This interview was originally published in the essay collection Forbidden Beat: Perspectives On Punk Drumming from Rare Bird Books (2022). The Rat Scabies conversation happened in 2021, before Scabies officially rejoined The Damned.

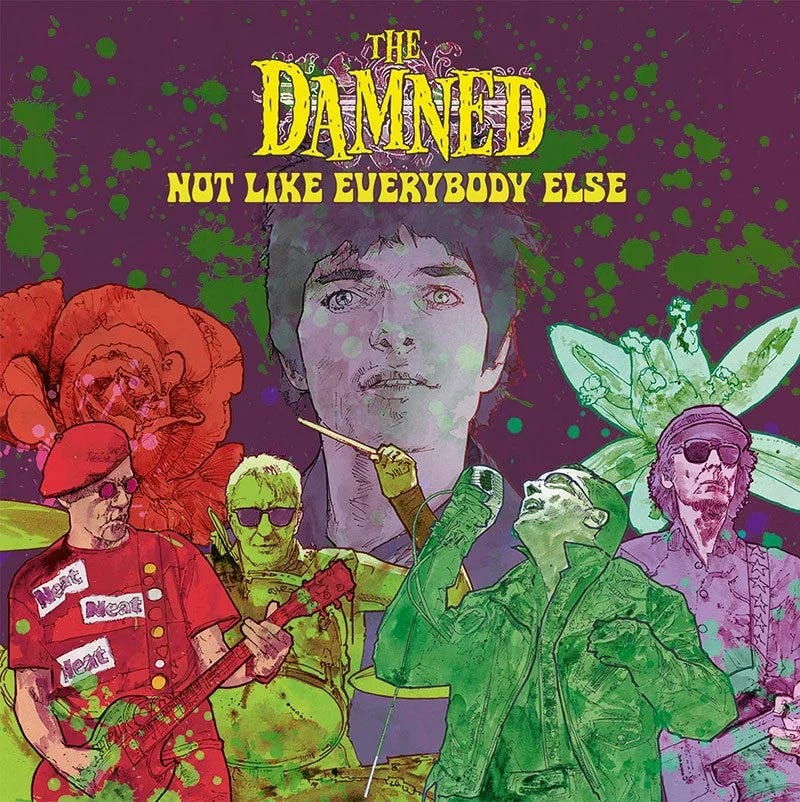

The Damned’s new album, Not Like Everybody Else (featuring Dave Vanian, Captain Sensible, and Rat Scabies recording in the studio together as The Damned for the first time in decades), arrives Jan. 23. The covers album is dedicated to Brian James, the band’s founding guitarist who died in March 2025.

The interview below mostly focuses on The Damned’s first few albums, along with some of Scabies’ other percussive exploits, and his overall take on punk and punk drumming.

I knew certain patterns and themes would emerge as I put Forbidden Beat together.

So, it was no surprise when many contributors name-checked The Damned’s Rat Scabies. He and guitarist Brian James founded the band in 1976, quickly adding vocalist Dave Vanian and bassist Captain Sensible to form the original line up.

The Damned was the first UK punk band to release a single, “New Rose,” and the first of their peers to tour the US. Scabies played with The Damned (off and on, in various line ups and musical phases) into the ‘90s, and on several studio albums including the punk classics, Damned Damned Damned (1977) and Machine Gun Etiquette (1979).

Let’s give Rat Scabies the last word…

When did you start playing drums?

Rat Scabies: I fell in love with the drums when I was about eight, the sound of the toms and cymbals. It’s that moment when you have a reaction to something and it just takes over. There’s no real logic to it, it just kind of bites in. I wanted to be a drummer, so I did everything possible to get close to it. But it was much harder then, because you couldn’t go get lessons. I was ten or eleven years old trying to find somebody to teach me, but nobody wanted to.

“If you pick up a guitar, you can play a Ramones song in as many minutes as it takes to listen to it. That inspires people to keep going... There’s a lot to be said for it being dumb.”

So, I joined the school orchestra, which immediately gave me a trumpet; then I joined the Sea Cadets, which immediately gave me a cornet. I was like, ‘I want to be a drummer!’ And they were like, ‘Cornet players are what we need. Everybody wants to be a drummer.’ But I was lucky in a way—I didn’t learn how to read music, but I got an understanding of how notes worked.

Who were some early drumming influences?

Rat Scabies: Anything with a lot of drums. There was a lot of jazz when I was a kid and, as I never tire of saying, jazz is great because there’s a drum solo in every song. So, there was always something for me to look forward to. I had a great big band album with Gene Krupa on it, and some Glen Miller stuff. Anything that was overly percussive, that’s what I wanted.

If I didn’t have to play with other musicians, I never would have done so—what would be the point? But at a certain point I listened to Sandy Nelson and realized even he, a guy who played tunes on tom-toms, had a guitarist. It was a sudden realization that maybe the rest of the world didn’t love drums quite as much as I did, and that maybe you needed to have something else going on until the next big drum moment.

It’s interesting you mention Gene Krupa, since he was a big influence on Jerry Nolan from the New York Dolls and the Heartbreakers.

Rat Scabies: The thing about Krupa was he was attainable. You could hear what Krupa did and it was musical, it made sense. As opposed to his arch-rival, Buddy Rich, who was just terrifying. You’d hear him play and you’d be like, ‘I’m going to go burn these sticks now. Why did I ever think I could do any of this?!’ With Krupa, you can just listen. Same thing with Sandy Nelson, it’s that ability to bring melody out of the drum kit.

A lot of other realizations come out of that, especially with Krupa. For him it was all about playing with the band and supporting what’s going on around you. When you get those four bars, twirl your sticks, and make it look fucking great, show off as much as you can, and then go back to playing the song. Krupa single-handedly made it seem like the drummer held the whole band together.

“I think The Damned didn’t really have anything to lose. We knew a lot of people weren’t going to get it, but, for some reason, that was what we were going to do. I always felt like we were doomed to failure, but what did I know?”

So, I would say Krupa was always the bigger influence on punk drummers. Which is why I think punk sustained so long, it’s the simplicity. If it’s too difficult or too technical, you just get disheartened as a beginner. If you pick up a guitar, you can play a Ramones song in as many minutes as it takes to listen to it. That inspires people to keep going and go on to bigger and better things eventually. There’s a lot to be said for it being dumb. [Laughs]

How did you make the transition from listening to jazz to what eventually became punk?

Rat Scabies: I could never play jazz. It was something that was always beyond me. I can just about bluff my way through it now, but it was always just sort of around. Then, after jazz, everything became blues. Mitch Mitchell, John Bonham—all those guys were jazz drummers. I mean, Keith Moon was probably the only one who wasn’t.

The blues explosion was all about the guitar, but later on you started to get the drummer and guitarist combos where there was complete empathy between the two—Jimmy Page and John Bonham [Led Zeppelin], Pete Townsend and Keith Moon [The Who], Eric Clapton and Ginger Baker [Cream]. And those were the bands that were big at the time, so when The Damned got going, I think it was very logical that Brian James and I were in that headspace.

It’s been said that American bands like New York Dolls, Ramones, and The Stooges had a big influence on early English punk. Was that true in your personal experience?

Rat Scabies: I kind of lived under a rock, I was suburban. I’d heard of the New York Dolls and the Stooges. I think I’d seen both of them on TV once and they were kind of okay, but what made me go ‘wow’ were MC5. There was something about Dennis Thompson, his timing, and those machine gun snare rolls. I could never do it. I tried and tried, but there’s just something about the way he did that. Brian James, however, was very clued up on those guys. Especially their attitude—this idea that perfection is over-rated.

So, Dennis Thompson was a favorite, but Tommy Ramone was the guy for me. The way he put his parts together was absolutely perfect. Again, playing the tune.

And he wasn’t even a “real drummer.”

Rat Scabies: Shhhhhh! You’ll ruin everything.

“You don’t start playing music so you can do the same thing for the rest of your life. It’s one of those sad ironies that you go on stage and people really only want to hear your previous work.”

Who were some of your favorite drummers among your early English punk peers?

Rat Scabies: I always really liked the way Paul Cook [Sex Pistols] played. Something about the way he went about it, he was rock solid and always played the right things in the right places. And I always liked what Jet Black [The Stranglers] did, because what he played was always kind of interesting. It wasn’t necessarily my style, but that guy knew what he was doing. And then Topper Headon [The Clash], of course, could always play full stop. I was the guy who flailed around a lot, but Topper was always solid. He’s very Jim Keltner in a way. I’m sure I’ve left a few people out. Then I marched in and was like, ‘Get out of my way! I’ll show you how this is done. This is what drums are for.’ [Laughs]

I think there was still this element of musicians wanting to be taken seriously by their peers and the audience at the time. Whereas I think The Damned didn’t really have anything to lose. We knew a lot of people weren’t going to get it, but, for some reason, that was what we were going to do. I always felt like we were doomed to failure, but what did I know? I loved playing with Brian, and I loved Dave and the Captain and being in a band with them, but, you know, I thought it was going to last about three months. I thought, ‘Nobody’s going to like this. It’s not like anything else out there, so of course nobody is going to buy this.’

Your drumming progresses rapidly over the first three albums, from the raw sixties garage beats on Damned Damned Damned to the much more dynamic playing on Machine Gun Etiquette. Were you aware of that at the time, or was it all happening too fast?

Rat Scabies: By the time we got to Machine Gun Etiquette, we were ready for a different approach to what we did. We didn’t just want to be a three-chord punk band that repeated the same formula on every record. We enjoyed the whole creative process and trying something like the piano on the beginning of ‘Melody Lee.’ I remember Captain saying that he didn’t know if the punters would like it because it was a bit slow. I was like, ‘It’s okay, it doesn’t last for long. They’ll forgive us. Just as long as we suddenly speed it up, they’ll be good with it.’ We realized that with things like the intro to ‘Smash It Up,’ too. And our audience were actually ready to move along at the same pace we were, which was our saving grace because if they weren’t we’d have been high and dry.

You don’t start playing music so you can do the same thing for the rest of your life. It’s one of those sad ironies that you go on stage and people really only want to hear your previous work. They don’t want to hear anything new because it’s not established, but you can’t establish it because nobody wants to hear anything new. So, it does sort of go against you in that sense. But I couldn’t stay the same. This is why I always tried to get involved in projects that people didn’t think would suit me or that you wouldn’t think I would do, because I like the challenge of having to play with Donovan. Suddenly everything’s very quiet, and it’s ‘Mellow Yellow,’ but it’s a challenging thing to do. It’s all part of what being a musician is.

“The thing about technical players is that you’re always really impressed by their brilliance, until you go into the next club where there’s a very similar drummer doing very similar things. There’s no uniqueness in that.”

It’s like Bowie said, if you can push a musician a little out of their comfort zone, then the end results are far more interesting. You’ve got the choice, you can either take a run and flying leap at it and hope for genius and brilliance, or you can fall flat on your face like some complete cunt. You’ve always got a fifty-fifty chance, so I always take the flier if I can…and hope to be held up as a genius. But the truth is it’s just another bluff.

From the perspective of somebody who was there from the start, and still playing today, what do you make of the many ways punk has evolved and mutated over the decades?

Rat Scabies: I think the most interesting thing about punk’s mutations is that everybody seems to have a different idea of what punk is. I swear, the next fucker who tries to tell me what ‘punk rock ethics’ are, I’m going to fucking punch them.

I’ve heard it all, but in a funny way they’re all right. Everybody takes the bit they like best and presents it as the thing punk was built on. But the truth is it was built on sand, it was built on absolutely nothing. And in a literal sense. We had nothing, so we made clothes ourselves—we’d wear bin-liners and dog collars. Society didn’t have room for us, and we couldn’t afford their society. If you give us nothing, that is what you’re going to get back. And we gave them nothing by the bucket-load.

But I do like the way punk ethics rubbed off on a lot of bands. Like Green Day. I met them very early on in their career and thought they sounded a bit like The Clash. Then I went to see them a couple of years ago in London and they were fucking brilliant. They’re just so good at what they do.

“You can always teach somebody to play, but you can’t teach them to be fun, or have ideas, or think laterally. And only ever please yourself. Make records that you want to make, that you think sound good, and not because you think it should sound like your biggest influence.“

Punk drumming has undergone some radical stylistic changes over the last couple decades. Is modern punk music recognizable to you?

Rat Scabies: It’s all technique. I listen to speed metal bands and wonder how they do that with their feet. Some of what these guys do is fucking incredible. It’s beyond Buddy Rich. It’s another method, another trick that you can master. What I do find really interesting is that there’s a lot more going on with arrangements now. I think performance has kind of reached its peak.

But the thing about technical players is that you’re always really impressed by their brilliance, until you go into the next club where there’s a very similar drummer doing very similar things. There’s no uniqueness in that. So, you end up with two schools. There’s [technical mastery], or you can try to push your imagination as far as it will go—which always sounds fucked up because it’s new and different because nobody has anything to compare it to.

Do you see any connection to what was happening in the seventies?

Rat Scabies: There isn’t a connection, really. What we did was blood and sweat. Nobody taught me how to do a one-handed roll. Like I said, you couldn’t get lessons, so you learned to play on pillows and cushions. Everything was single stroke. If you used technique, it was much quieter and didn’t really count for much. And years later you realize how right you were when a recording engineer puts a noise gate on your snare. It’s like, ‘I spent two years learning how to do that paradiddle flam ghost and you gated it out.’ And the engineer’s like, ‘I just want it to go crack. I don’t need all that frilly stuff, it’s just getting in the way.’ I think it’s very easy to waste a lot of time doing things that never get heard.

Any advice for a young drummer looking to start their first punk band?

Rat Scabies: The only advice I ever give anyone is to make sure you do it with people you like. You can always teach somebody to play, but you can’t teach them to be fun, or have ideas, or think laterally. And only ever please yourself. Make records that you want to make, that you think sound good, and not because you think it should sound like your biggest influence. It’s really important that you please yourself and do it with people you can hang out with because you’ll end up sitting next to them in the back of a tour van for nine hours, so you better be able to talk to them.

The bit about Krupa being attainable versus Buddy Rich being terrifying really captures why punk's simplicity was its superpower. I remember trying to learn jazz beats and just getting crushed by the complexity, but then hearing Ramones and realizing the whole point was to strip it down to what actually moves people. The way Scabies talks about supporting the song rather than showing off technical chops feels like wisdom alot of modern drummers could use, especially in genres that have gotten so tech-heavy they forgot what made punk compelling in the firstplace.