Some of the charred metal drum remains from the rubble of our garage.

S.W. Lauden is my pen name. The person behind it is Steve Coulter.

My family and I sadly lost our Altadena, CA home to the Eaton Fire. We are all safe, but the road ahead will no doubt be difficult.

These “Vodka Sauce” posts are more Coulter than Lauden, but I’m trying to spread them out between our regularly scheduled “music, books and music books” programming.

The rafters and shelves of our Altadena garage were stuffed with drums when the Eaton Fire burned it all down.

I’ve played in punk and rock bands since high school, getting active again in recent years with The Brothers Steve and a reunited Ridel High, but nowhere near enough to justify the small drum shop worth of gear I’d accumulated.

The last inventory found five drum sets, four snare drums, 10 cymbals, 25 stands, several cases, and more tambourines, maracas, and rhythm eggs than you could shake a stick at. There were too many personal memories attached to a lot of that gear to ever imagine letting it go—including the custom Pork Pie drum set I used in Tsar, still in the spray painted cases we hauled all around America in the early 2000s.

Our daughter Lucy bashing away on my sparkly red, white and blue Tsar drums at a rehearsal space in 2011. This video is a great reminder that losing those drums was about a lot more than playing in a glam punk band.

Reckoning with that was the furthest thing from my mind in those first few days, but a friend immediately reached out to offer me a drum kit.

I was too dazed to process his kindness until our family was on the sullen drive from my mom’s house to a series of post-fire AirBnBs in the foothills. I suddenly blurted out: “This is the first time I haven’t owned a drum set since I was twelve!”

The fact that I was drumless felt like a startling realization in that moment.

Sadly, I’m not alone. Based on conversations with local friends and social media posts I’ve seen, a lot of personal musical history went up in flames when our town burned down (including the keyboard both of our daughters took piano lessons on).

The latest reporting says that a staggering 6,000+ homes, multi-family dwellings, and businesses burned down in the Eaton Fire. Another 1,000+ dwellings, businesses, and structures were damaged.

It sounds like many of those buildings were home to musical instruments.

A blackened drum key and molten, fused hi-hat cymbals found in the ashes of our garage.

Situated on the wild outskirts of LA’s urban sprawl, Altadena was paradise for semi-feral musicians looking to put down roots.

A sad and timely post in the Beautiful Altadena Facebook group really sums up the artistic spirit of this community: “My FEMA reservist called today for a follow up and made a point of saying ‘Almost everyone (he has) talked to in Altadena had some kind of musical instrument or some type of art that they lost. This must have been the most amazing and talented community and I’m so sorry for your loss.’”

It’s totally true. I count can’t the number of times I was introduced to other musician neighbors at school events or backyard barbecues. From rock, pop and soul, to jazz, country and beyond, these foothills reverberated with the sounds of local music.

And, of course, there are the many old rocker pals who lived nearby.

That includes Jeff Solomon, my longtime bass counterpart in Tsar, Ken Layne & The Corvids, and The Brothers Steve. He and his family lost their beautiful old home just to the east of ours, along with most of Jeff’s music equipment.

“I dug for a while trying to find a tuning peg—or anything—but no luck,” Jeff told me after visiting the remains of their house for the first time earlier this week.

Bass players and drummers often develop deep, personal bonds. I know that Jeff and I definitely did. So, picturing my old partner in crime sifting through the ashes of his home searching for bass fragments just about snapped my charred heart in two.

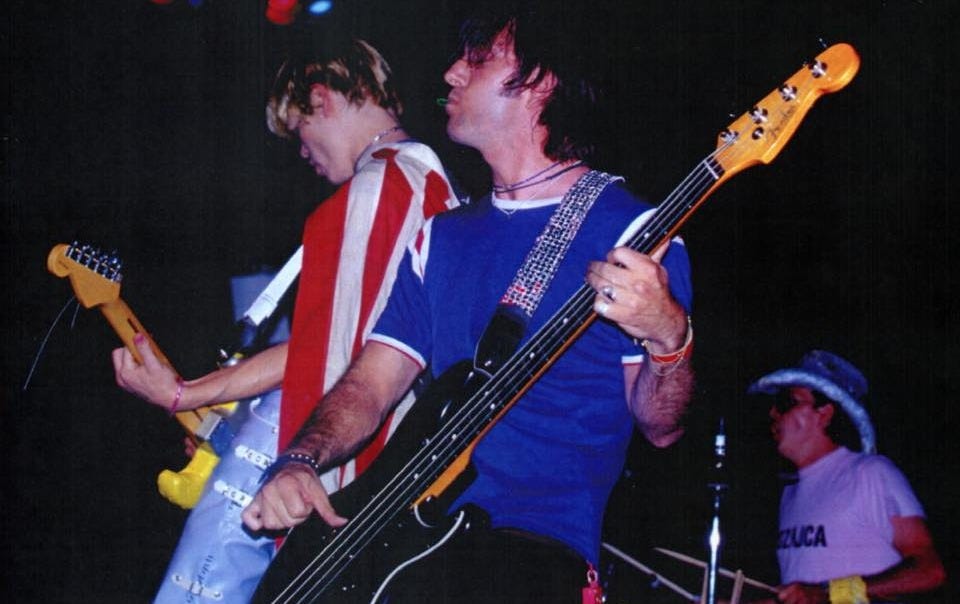

Jeff Whalen, Jeff Solomon and Steve Coulter (aka me) of Tsar in 1999. That black Fender P-Bass was one of many instruments lost in the Eaton Fire. My totally cool cowboy hat and mirrored shades are gone too, along with all of my Tsar memorabilia. Photo by Piper Ferguson.

A little further west, Marko DeSantis of Sugarcult, Bad Astronaut and, more recently, the Ridel High reunion line up, also lost most of his lovingly curated equipment when his family’s home burned down.

Just two nights before the fire, Marko remembers telling a friend how he still had the yellow plastic string winder and old wire cutters he got along with his first guitar as a teenager. Those two precious tools of the trade traveled with him around the globe and across decades…until they were finally destroyed in early January.

“I was out of town and didn’t want to burden my wife and daughter with trying to sort through my gear, so I lost everything except these two guitars I had loaned to two of my friends with recording studios a while back and (luckily!) never bothered to retrieve,” DeSantis told me.

Marko and I had a Ridel High show booked in Santa Barbara with our buddies in Nerf Herder on January 18th.

The line up for that gig included our friend Justin Fisher, another displaced Altadenan. His family’s home is thankfully still standing but unlivable due to toxic smoke damage. We canceled our slot when we realized that 3/5s of the band had been directly impacted by the fires—and that Marko and I no longer had gear to use.

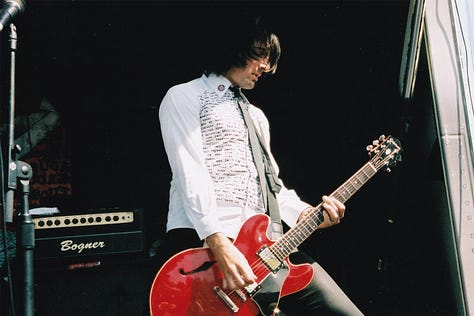

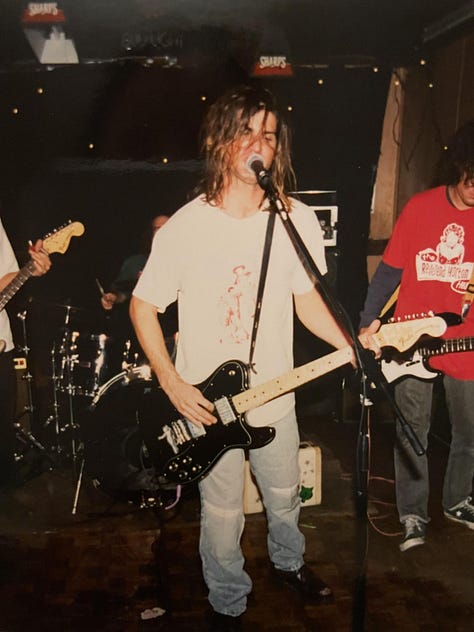

“I lost a red (335) semi-hollow body, my main guitar for Sugarcult’s peak era in the early 2000s. It’s featured in a few of our music videos, when we did Late Night with Conan O’Brien, and I played it on arena tours we did with Green Day in America and Blink 182 in Europe, as well as countless other shows, festivals, TV appearances,” he said. “Also, my trusty black ‘73 Fender Precision bass. I bought it back in the early ‘90s and it was a mainstay throughout my Popsicko era.”

Marko with Sugarcult in the early 2000s playing his red (335) semi-hollow body; Slinging his ‘73 Fender Precision bass with Popsicko in the early ‘90s; The back of the P-Bass that Marko carved the night he found out Popsicko’s frontman Keith Brown died in 1995.

A couple of days ago I got an unexpected call from Brandon Jay (aka Quazar), another musician friend from the ‘90s.

He and his wife/talented musical collaborator, Gwendolyn Sanford, lost their Altadena home, recording studio, and all their gear in the Eaton Fire. I first met Brandon when he was a fixture on the Silverlake music scene, playing in bands like Lutefisk, The 88 and, for many years now, fronting Quazar and the Bamboozled.

Brandon was calling to tell me about an epiphany he had after sitting in on percussion with his friend’s band Generic Clapton at a Sierra Madre bar on January 18th, and a performance by the Bamboozled as part of the Pasadena Neighbor Day concert at the Wild Parrot Brewing Company the following afternoon.

“Tonight I got on stage for the first time since the fire that destroyed my home,” Brandon wrote on Facebook in the wee hours of Jan. 19th.

Quazar and the Bamboozled perform the Talking Heads’ “Burning Down The House” at Pasadena Neighbor Day on Jan. 19th: “I mean no offense by this. Please, this is me—in my anger and angst—needing to get this out of my body.”

He said the experience was “incredibly joyful, emotional and cathartic.”

“A batch of friends let me borrow or gave me percussion to use at the gig. As I was picking through a bin of foreign instruments deciding what to play on each song, I started thinking about the instruments that my wife and I lost. What gave most of them great value was the stories behind them and how they came into our possession.”

Brandon listed several pieces of equipment along with personal memories: an acoustic Ibanez guitar his uncle gave him as a teenager; castanets from Kim Shattuck of The Muffs; the Baldwin piano he and Gwendolyn got on Craigslist and on which both of their children took lessons, among many other touching tales.

The realization he had after playing those shows—coupled with the overwhelming response to his Facebook request for friends to donate instruments and give him new stories—was quickly snowballing into a new non-profit organization.

“We’re working on a website so that you can list all the gear that you lost and other people can donate and get as much of it back to you as possible,” Brandon texted Jeff Solomon and I to explain the simple vision for Altadena Musicians. (The website is still a work in progress, but they will have an official launch soon.)

A Ridel High reunion show in 2024 (L-to-R): Matt Fuller, Steve Coulter (aka Lauden), Kevin Ridel, Marko DeSantis and Justin Fisher. Photo by Steve Rood.

I feel ambivalent about replacing my gear.

Struggling with the loss is one thing, but the thought of the time and energy it would take to find similar drums, stands and cymbals feels exhausting. Not to mention the emotional connection I had with all of the equipment I’d acquired since the ‘80s.

I’ve seen the generous offers of help from organizations like the Guitar Center Foundation and MusiCares, but haven’t felt motivated to sign up. The insurance paperwork, legal consultations, long-term rental applications, contractor/architect conversations, and my ongoing job search have all kept me plenty busy. It’s a lot.

I quickly discovered I’m not alone in those complicated feelings after connecting with my musician pals, but that’s just a small group of impacted people I felt comfortable reaching out to. There are many others around Altadena with similarly tragic stories.

“It hurts twice to lose instruments—once for the residue of memories they co-piloted imbued in them over time, another for their unique sonic nuances and characteristics,” Marko said.

“There’s no way to fully ‘replace’ such sentimental gear, but I’ll never stop playing music, so I’m sure I’ll get my hands on some gear sooner or later. I already broke strings on both of the cheap, decorative guitars they have hanging on the wall of the bar in the lobby of the hotel where we’re staying for now…so I’m gonna have to figure something out!”

I think we all will. Thankfully, there are people like Brandon—with his expanding network of non-profit partners—trying to make it happen sooner rather than later.

It’s starting to sound like I won’t be drumless for very long.

This is unbelievably heartbreaking.

Give me your address. I demand it!

davefrancodrums@gmail.com