Big Star’s “September Gurls” is easily one of the best power pop songs of all time.

The chiming mando-guitar that opens the track might be the distilled essence of the genre itself, but the song really starts to soar with the single bass note, mournful guitar lick and simple drum fill that herald the first verse.

From the opening line, Alex Chilton’s evocative vocals cut right to the heart of love, loss and longing in a way that feels utterly relatable—even if you have no idea what he’s actually singing about:

September gurls do so much

I was your butch and you were touched

I loved you, well, never mind

I've been cryin’ all the time

That mysterious specificity (“I was your butch…”) draws you in, while the emotional dismissiveness (“I loved you, well, never mind…”) demands personal interpretations. Then the sucker punch lands (“I’ve been crying all the time…”) and there’s no doubt this is a song about heartbreak as it heads into the chorus:

December boys got it bad

December boys got it bad

I’ve been a butch for “September Gurls” since I first heard it in my teens, more than decade after it was first released by Ardent Records in 1974.

At the time, its staggering genius was almost impossible for me to comprehend, like having a religious experience before your first communion. And as is the case with so many Big Star fans, my relationship with “September Gurls” has only grown deeper over the course of countless listens:

September gurls, I don't know why

How can I deny what's inside?

Even though I'll keep away

They will love all our daysDecember boys got it bad

December boys got it bad

In particular, I’ve always been fascinated by the chorus lyrics about “December boys” in a song titled for the objects of their affection. For a very long time I was convinced that “December boys” was Chilton’s poetic way of collectively describing lovesick teens—a group I certainly belonged to during my high school years.

More specifically, my theory was that “September Gurls” referred to young women who went off to college while their blue collar boyfriends stayed behind in their hometowns, waiting for them to return over winter break.

It wasn’t until I read Holly George-Warren’s biography, A Man Called Destruction: The Life And Music Of Alex Chilton From Box Tops To Big Star To Back Door Man, that I realized a missing apostrophe might change my whole conception of the lyrics.

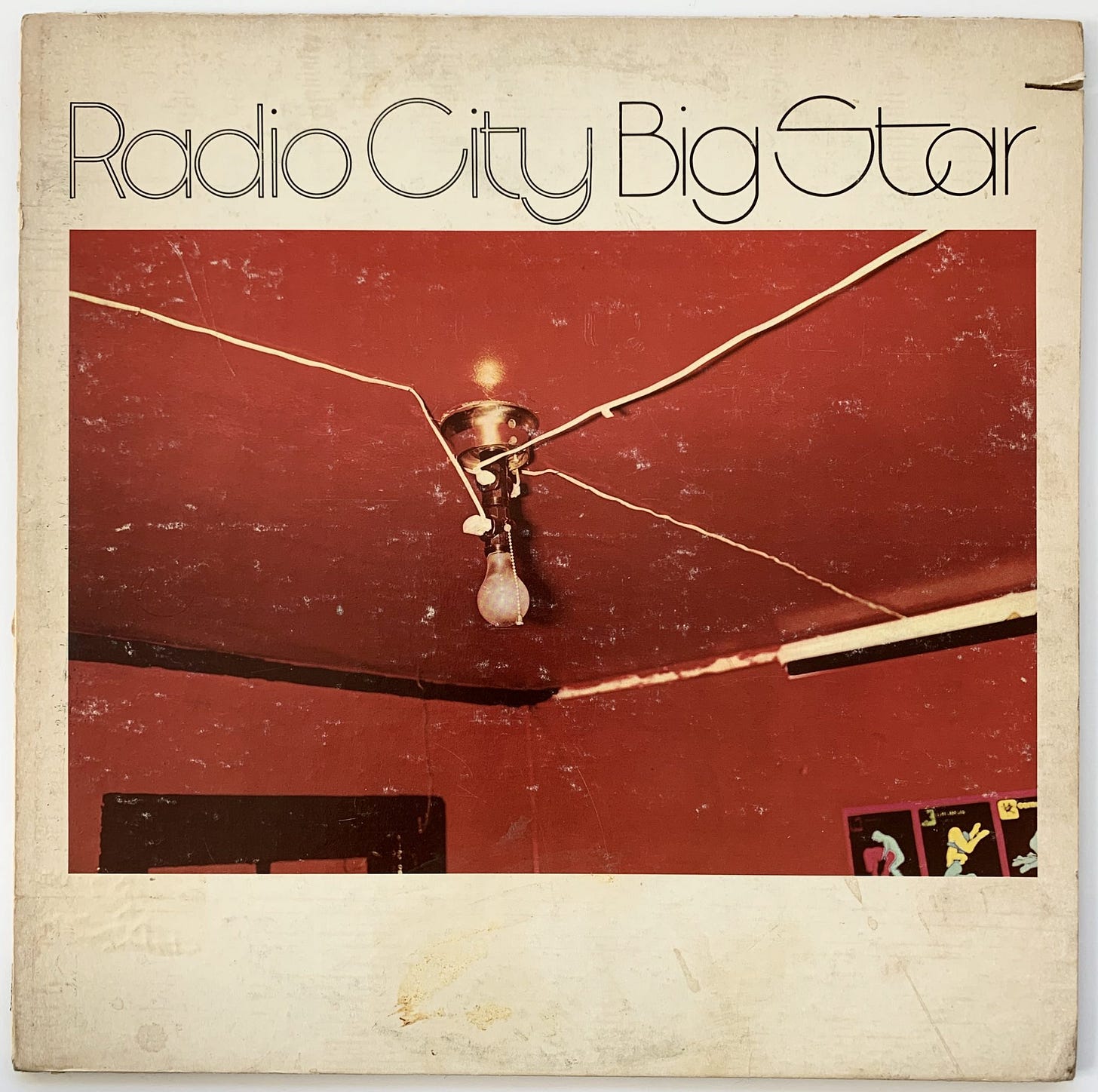

“The last song Alex, Jody, and Andy recorded together for the new album [Radio City] summarizes everything Alex had been going through that summer, both musically and emotionally. Women were on his mind, including his ex-wife, Suzi, who had left Memphis with Tim Benton and Timothee for Texas; Vera, back and forth from Colorado; and Diane, now seeing other guys. They had one thing in common: All three were born in September,” George-Warren writes.

The author follows up with this quote from Chilton: “I’d never had an easy relationship with a woman that didn’t degenerate into some kind of deception or bad feeling. I always wrote about what was happening to me.”

Chilton’s birthday is December 28 which led some fans to speculate that the line could be interpreted as “December boy’s got it bad”—as in “December boy HAS got it bad.”

Coming across the missing apostrophe theory—and that’s really all it is, a low level fan theory—was a thrill for me because I briefly got to reconsider one of my favorite songs from a different perspective. (Interestingly, you see both spellings on the internet. More definitively, there is no apostrophe in Big Star’s official lyric video for “September Gurls,” but they also spell “September girls”with an “i,” so…)

Adding to these lyrical revelations, Big Star drummer Jody Stephens told Mojo magazine that “I was your Butch…” (with a capital “B,” like it is in the lyric video) refers to a DC Comics puppy, evoking images of Chilton following his “September Gurls” around in a lovestruck daze. Jim Duckworth, a future collaborator, also mentions that “Butch” was Chilton’s nickname in A Man Called Destruction.

Does all of that make a strong case for the missing apostrophe? Probably not, but it’s fun to think about for a little while. Does it even matter? Depends who you ask.

This kind of lyrical dissection is like a drug for nerdy music fans seeking clues about their own experience while stealing glances into the interior lives of their musical heroes—but it’s also a two-way street.

There’s the song the artist wrote and put out into the world, and then there’s the personal interpretations each of us brings to it. It’s very rare for the two to align.

In that way, music is like a delayed collaboration between creator and interpreter. A crackly long-distance call between strangers who don’t speak the same language. It’s a lifelong dance with a specific piece of art that gets more meaningful as it ages.

All of which might be completely different from the artist’s relationship with the song.

Chilton, a noted iconoclast who never seemed to fully buy into the romanticized mythology that developed around Big Star in the ‘80s, had this to say about “September Gurls” in A Man Called Destruction:

“The musical structure’s fine, it’s the lyrics that were the odd bit for me at that time. ‘September Gurls’ may be one of the more coherent things that I managed to produce in that time but if I were more confident in writing lyrics I probably would have done something else. It’s not a song that really grabs me to this day. The musical structure grabs me but the overall song doesn’t—and that’s the way I feel about every bit of music on that record.”

Respectfully agree to disagree.

By contrast, here’s what Bruce Eaton wrote about it in his 33 1/3 book about Radio City: “One of the greatest hits that never was, ‘September Gurls’ practically demands that when the record is over, you reach for the replay button. It embodies the franchise Big Star power pop sound—often imitated, never duplicated.”

In his thoughtful song-by-song break down of the album, Eaton says the instrumental break after the bridge sounds like “the house band in power pop heaven.” (And I’ll add that it features an iconic drum fill from Stephens who turns in a truly incredible performance throughout the track that doesn’t get nearly the praise it deserves.)

“There’s nothing technically flashy—just two simple ringing guitar parts, straightforward bass and drums in the best McCartney and Starr fashion, and angelic yet wistful background vocals—all bathed in a warm, glowing sound that makes you feel as if the band is right in the room surrounding you, not on some distant stage behind an invisible barrier of studio effects,” Eaton writes.

Not only is that a powerfully written description of a musical passage that only lasts twenty seconds, but it gives you an idea of just how nuanced the analysis of this song can get. I imagine this is how diehard Beatles fans feel about pretty much everything the Fab Four ever released; but let’s be honest, the Venn diagram of Beatles fans and “September Gurls” fans is probably damn near a flat circle.

How can I deny what's inside?

Much as I love music, I’m really only this devoted to a few dozen songs including “Waterloo Sunset” by The Kinks, “Alone Again Or” by Love, “Five Years” by Ziggy Stardust, “Dancing Barefoot” by Patti Smith, “Unsatisfied” by The Replacements, “Elephant” by Jason Isbell—and, of course, “September Gurls.”

Part of me scoffs at the obviousness of that list, but that’s the point—they’re obvious to me because they are part of the hand-selected soundtrack to my life. Outside of some musical, lyrical and stylistic commonalities, the connective tissue is me.

Even when I get the lyrics wrong or misunderstand the songwriter’s intentions, I can always go back and get to know the song all over again—and that’s pure magic.

What a difference an apostrophe can make.

⚡️💥 CHECK OUT THESE GREAT GUEST POSTS…

The Power Pop-Adjacent Comfort Blanket

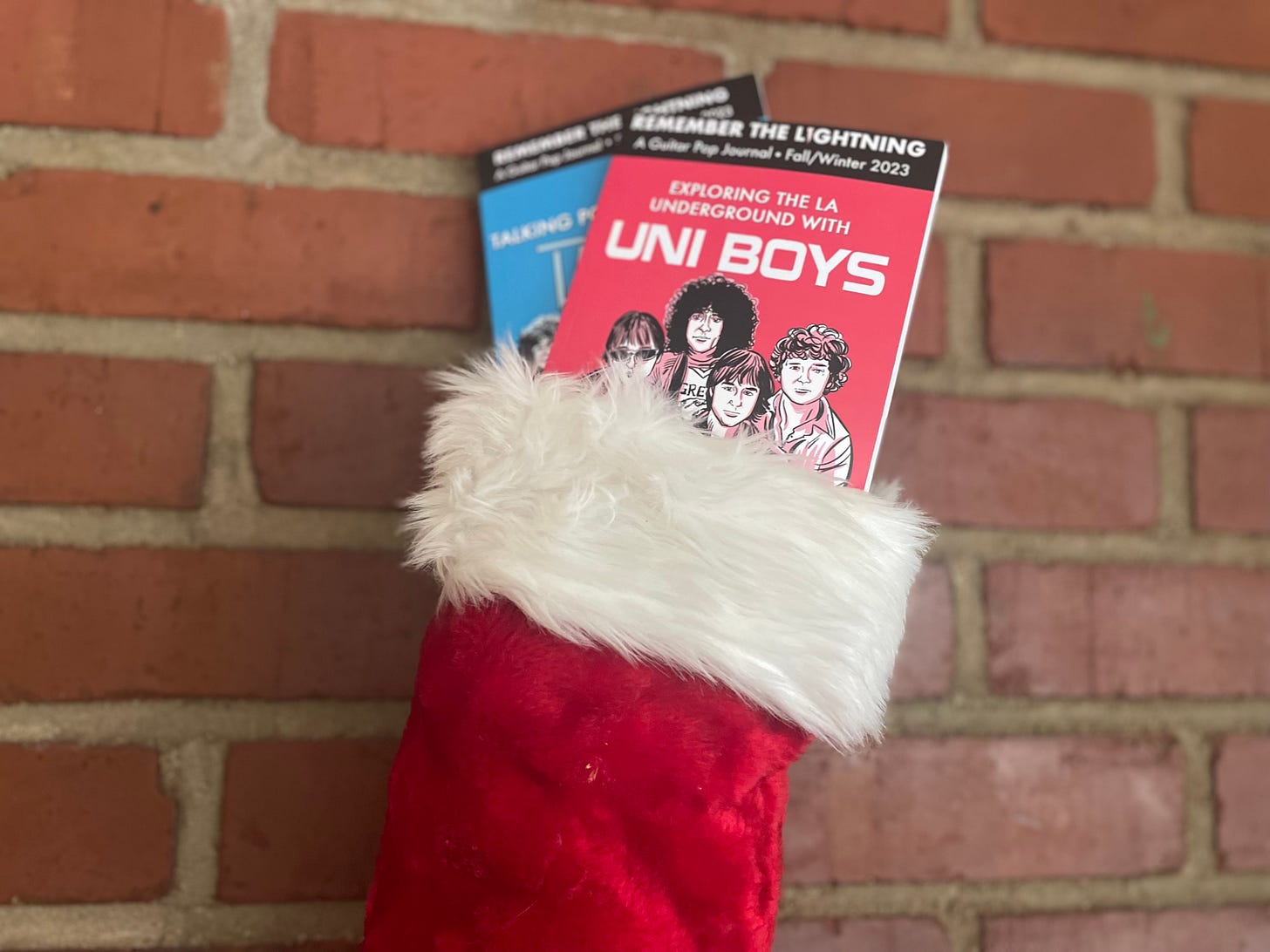

To celebrate the release of Remember The Lightning: A Guitar Pop Journal, Vol. 2 (the red one with Uni Boys on the cover!)—and to help spread the word about Dazy’s current tour dates (see below)—we are sharing James Goodson’s excellent essay from Remember The Lightning: A Guitar Pop Journal, Vol. 1

Sloan: The View From Here

We’re excited to share an exclusive excerpt from Remember The Lightning: A Guitar Pop Journal: Mary E. Donnelly’s exploration of Sloan from the perspective of an adult fan. Mary is a talented writer whose thoughtful approach to the legendary Canadian power pop band is truly unique. The excerpt below is only the intro to ‘Sloan: The View From Here’; the …

Putting The P💥W! In Power Pop

Today I’m thrilled to share one of my favorite essays from Go All The Way: A Literary Appreciation of Power Pop (Rare Bird), the collection I co-edited with Paul Myers. I had originally intended to write this essay myself, but after getting to know Ira Elliot—drummer for Nada Surf and Bambi Kino—I was more interested in he…

I've been known to put "September Gurls" on repeat in the car and drive all day with just that song.

That was a fun read. For some reason, it reminded me of a story from my days as a newspaper editor. At the time, I was an AP style hound and got into an argument with an English major who was one of my reporters over the use of the serial comma. The argument — we truly did not like each other — became heated and prompted the publisher of this small-town North Carolina newspaper to pose the question: "Really, do you think our readers give two shits about the serial comma."

For once, the reporter and I agreed as we said in unison: "They should."