Putting The P💥W! In Power Pop

GUEST POST: Ira Elliot ('Go All The Way' Book Excerpt)

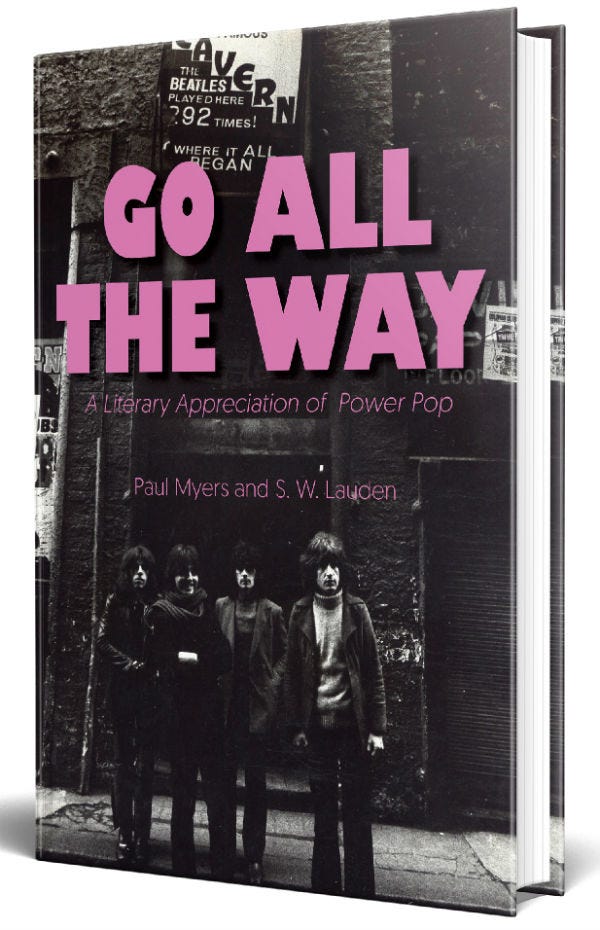

Today I’m thrilled to share one of my favorite essays from Go All The Way: A Literary Appreciation of Power Pop (Rare Bird), the collection I co-edited with Paul Myers. I had originally intended to write this essay myself, but after getting to know Ira Elliot—drummer for Nada Surf and Bambi Kino—I was more interested in hearing his thoughts on power pop drumming. I definitely wasn’t disappointed, and I don’t think you will be either.

Putting The POW! In Power Pop

By Ira Elliot

Trying to get a handle on power pop is not as easy as one might think. For all the usual suspects like Badfinger and Raspberries, Matthew Sweet and Fountains of Wayne, there are dozens of lesser-known bands approaching the genre in myriad ways.

Dreamy and psychedelic like the Posies, fast and furious like the Dickies, even big artists that we don’t generally think of as power pop occasionally dabble in the genre. Billy Joel’s “All for Leyna,” Springsteen’s “Radio Nowhere,” the Clash’s “Safe European Home,” and Queen’s “Need Your Loving Tonight” fit easily under the big, polka-dot power pop tent.

But despite surface differences, all of these four-minute tales of love and loss, yearning and frustration, togetherness and loneliness, do share a few structural similarities. Underlying the catchy melodies, chiming guitars and thumping basses lay the more obscure and mythical domain (Valhalla? Camelot? Bayonne?) of power pop drummers.

It’s safe to say that any power pop drummer has two primary sources of inspiration: Ringo Starr and Keith Moon. They are the yin and yang of power pop drumming—Starr representing the more calm, structured, adult approach; Moon the wild, rebellious, teenage id.

You can hear this dynamic in the playing of one of power pop’s earliest and most revered drummers, Big Star’s Jody Stephens. His drumming on songs like “September Gurls,” “Feel,” and “O My Soul” encapsulates the combination of solid timekeeping and loose, manic fills.

“At times I’m aware of my influences when I play drums. I’ll deliberately think, ‘I wonder what Ringo would have done here?’ Or I think, ‘What would Keith Moon have done here?’ But sometimes it’s not a thought as much as an impulse. Then it just sort of happens. It’s still derived from an influence, but it’s however that influence is instilled in you and how it comes out emotionally,” Stephens said by phone from Ardent Studios in Memphis, Tennessee.

“Coming up, when we all got together, I don’t think I’d heard the expression ‘power pop’... It seems like the term ‘power pop’ came along afterwards. We were just doing what we felt like doing,” he added.

The Shining Starr and the Raging Moon

Ringo Starr is clearly and quintessentially power pop. A steady, hard-hitting rock and roll drummer powering a catalog loaded with guitar-driven, melodic pop gems, his stylistic influence on all rock drummers is deep and across the board.

From the fanned hi-hats of “All My Loving” and the cracking snare of “Paperback Writer,” to the thumpy toms of “A Day in the Life” and the punchy bass drum of “Revolution.” These stylistic elements are central to power pop drumming.

I asked Ben Lecourt, who has collaborated with Emitt Rhodes and plays with Denny Laine of Wings and Joey Molland of Badfinger, to weigh in.

“Ringo is still the model, blue print for the perfect crafted part that will ‘wrap’ the song like a tailor would design the perfect jacket. What he’s done remains the best pop drumming lesson to this day,” he said.

And then we have Keith Moon, whose first love was surf groups like the Surfaris, Ronny and the Daytonas, and Jan and Dean. He’s probably best known for playing a lot of rapid-fire fills, those dynamic, aggressive flourishes that all drummers enjoy trying on for size...although most end up having to dial it back for fear of overplaying.

Watch live performances of the Who, however, and you’ll notice that Moon was acutely aware of the lead vocals, often singing along with Roger Daltrey. So what at first might appear to be arbitrary overplaying turns out to be a running commentary on the lyric. This is the reason his flashiness never takes away from what’s being sung, which is an important point.

Beyond the obvious stylistic differences between Starr and Moon, we see two players whose primary concern is for the song. Their focus on how best to frame the chords, melody, and words—to motivate and underscore the song’s intent—are core tenets that define all the greatest drummers.

“I’ve never really thought about what makes a good power pop drum track. I just think about what’s going to make a good drum track for this song. It depends on how the singer is delivering it because I listen a lot to the singer, and I listen a lot to the guitar player. I get more energy out of guitar players and singers, but it’s always nice to try and lock into what the bass player’s doing too,” Stephens said.

At thirteen, having just started to become a serious, teenage rock drummer myself, I spent most of my free time playing along with the radio or albums. By twenty-three, I theorized that you could learn everything you needed to know about this craft by listening only to Starr, Moon, Charlie Watts of the Rolling Stones, and John Bonham of Led Zeppelin—what I called “The Four Horsemen of Rock Drumming.” I’ll stand by that statement today, some thirty years on.

“I’ve met quite a number of people over the years who feel Ringo somehow doesn’t rate because his style is overly simple and devoid of “chops”—those slick, learned phrases that simply show how long a drummer has practiced alone in a room on a slab of hard rubber. To them I say, virtuosity is not a prerequisite.”

But we’re specifically talking about power pop here, a genre that really didn’t start to take shape until a few years into the seventies. So if we look at the drummers of that period more closely aligned with the poppy, snappy Starr and Moon—and less so the bluesy, funky Charlie and Bonzo—my “Four Horsemen of Power Pop Drumming” would likely be Cheap Trick’s Bun E. Carlos, Clem Burke of Blondie, Jimmy Marinos of the Romantics, and Bruce Gary of the Knack.

It’s interesting to note that my self-proclaimed Horsemen of Rock Drumming are all British while my Horsemen of Power Pop are all American. Which is to say it appears that the preponderance of big power pop bands—in some kind of karmic payback for the British Invasion—were American.

In my mind, 1979 stands out as the apex of power pop in the mainstream. Tom Petty’s Damn the Torpedoes; Buzzcocks’ Singles Going Steady; the Cars’ Candy-O; XTC’s Drums and Wires; ELO’s Discovery; Nick Lowe’s Labour of Lust; Elvis Costello and the Attractions’ Armed Forces; Joe Jackson’s Look Sharp!; Dawn of the Dickies; the Records’ self-titled debut; Bram Tchaikovsky’s Strange Man, Changed Man. I was sixteen at the time and to me it felt like a year-long power pop orgy.

A number of factors were in play here—the rise of new wave music, the 1977 release of the Beatles’ astonishing Live! at the Star-Club recordings from 1962, and perhaps a general sense of nostalgia for the sixties that had started earlier in the decade as a fascination with fifties culture and music. I spent the summer of 1979 like just about everybody else hearing Cheap Trick at Budokan blast out of the radio night and day.

Cheap Trick’s pounding rock was tempered by Bun E. Carlos’ loose-wristed style. His left hand often played eighth notes along with his right, ghosting the notes between backbeats like the great Earl Palmer, who is often cited as the architect of rock and roll drumming. (You can hear it very clearly on the opener, “Hello There.”)

This gave his playing a distinctive kind of old-school lope that was a signature part of Cheap Trick’s sound. Bun E.’s galloping tom fills and rock-solid backbeat are the perfect complement to Cheap Trick’s Beatlesque songs and a central reason why they became the world’s most popular and successful power pop band. “Dream Police,” also from 1979, is another fantastic showcase for Bun E.’s Starr/Moon expertise.

Clem Burke showed up to the power pop party overdressed and ready to throw down. Coming from the CBGB punk scene, the members of Blondie were all stylish characters but Clem’s love of high-collared shirts, four-button suits, and skinny, knit ties (Starr!) were perfectly matched by his remarkable red sparkle kits (Moon!).

“Dreaming” and “Union City Blue” from 1979’s Eat to the Beat are perfect showcases for his breathtaking machine-gun fills. His background in rudimental drumming, having played in a drum and bugle corps back in Bayonne, New Jersey, allowed him speed and agility around the kit.

“When it comes to power pop, the importance of the drummer’s attitude and energy cannot be understated. This is why I believe power pop has been and will continue to be a pursuit for musicians of any age, particularly young ones.”

Clem’s notable gift for showmanship is undoubtedly a direct reflection of his undying Keith Moon worship. His powerful style has allowed him to move effortlessly into the drum chair of a long list of other notable bands including the Ramones, Eurythmics, and Dramarama— not to mention the next band in the 1979 power pop canon.

Recorded late in the year, Detroit’s Romantics’ first album contains the power pop megahit “What I Like About You,” which fuses equal parts early Beatles, Yardbirds, Chuck Berry, Standells, and Neil Diamond.

It was Jimmy Marinos’ drumming—tough and propulsive, verging on hard rock—that helped make the record a pounding, dance floor staple.

“Part of the beauty of power pop drumming, like all rock drumming, is that it doesn’t necessarily require a high degree of technical skill. Rock and roll music is a folk art; you don’t need a degree from Berklee to make it.”

Sharing Clem Burke’s eye-catching penchant for setting his drums and cymbals completely flat, Marinos was also, like Starr, a lefty on a right-handed kit. But unlike Starr, he played open-handed instead of cross-handed, which allowed him a very powerful back beat.

Let’s also give Jimmy special mention for being the lead singer on this track, another power pop drumming rarity that he shares with Starr.

But more than any of these songs, 1979 was the year of “My Sharona.” Certified Gold and hitting number one on the US Billboard charts, “My Sharona” was a power pop juggernaut and when it exploded onto the radio, it was drummer Bruce Gary who lead the charge. The aggressive, flam-filled kick, snare, and tom intro, lifted from Smokey Robinson’s 1967 “Going to a Go-Go,” was absolutely undeniable.

Bruce was an LA session player who was capable of sounding wildly spontaneous while remaining completely airtight. There’s not one misplaced hit on any Knack song, but the performances are never mannered or stiff.

Unlike most recordings of late seventies where the drum sound was thumpy and dead, Bruce’s drums were bright and ringing, one of the reasons that Get the Knack was such a breath of fresh air. The longer, album version of “Sharona,” “Let Me Out,” and “Number or Your Name” are all textbook examples of how to channel Moon into a contemporary pop song.

“Artists are inspired by the things they love, and it’s hard to think of a more enduring love affair than the one we have with the Beatles. Young musicians will invariably attempt to write songs that somehow echo their style…”

In these four power pop drummers, we see both the solid timekeeping skills of Starr and the visceral enthusiasm of Moon. Of course, these four choices are admittedly a bit arbitrary since there are many other great drummers I would love to namedrop here. Topping that list is Jim Bonfanti, the Raspberries’ first drummer.

His remarkable rolling, tripping tom fills on “Go All the Way,” and particularly on “Tonight,” are nothing less than power pop scripture. Like Stephens from Big Star, Bonfanti fully inhabited the Starr/Moon nexus.

I’ve met quite a number of people over the years who feel Ringo somehow doesn’t rate because his style is overly simple and devoid of “chops”—those slick, learned phrases that simply show how long a drummer has practiced alone in a room on a slab of hard rubber. To them I say, virtuosity is not a prerequisite.

In my opinion, Ringo had something much more valuable—the confidence of someone who’d spent a lot of time getting rooms full of people to get up and dance. But he wasn’t fancy. He was bone simple, and this is what I call “The Tao of Ringo.”

Part of the beauty of power pop drumming, like all rock drumming, is that it doesn’t necessarily require a high degree of technical skill. Rock and roll music is a folk art; you don’t need a degree from Berklee to make it.

What you do need is a solid set of basic timekeeping skills, three-limb coordination (which I guesstimate can be developed in about the same amount of dedicated time it would take to be a passable skateboarder, let’s say) and, most importantly, musical empathy—an innate connection with and love of music that transcends skill. You simply need to be the right person for the job at hand, which may have as much or more to do with your personality as your ability.

“I think what’s key to the essence of power pop drumming is attitude and maintaining a youthful outlook and feel to one’s playing,” said Dennis Diken, drummer for the Smithereens. I was incredibly fortunate to work as a drum tech for Diken in the nineties and consider him to be one of the best power pop drummers ever.

“One of the greatest compliments I ever received was from John Duckworth, the drummer from Syndicate of Sound whose ’66 snotty, jangly, round-the-kit fill-laden ‘Little Girl’ was a major air drum record for me when I was nine years old. He said, ‘Hey, I was watching you play, and I can tell you’re a talented drummer but man, you played that set like you were seventeen!’ I was forty-three at the time. I’m a few years on now, but I still try to keep that teenage spirit burning whenever I get behind the kit with the Smithereens.”

When it comes to power pop, the importance of the drummer’s attitude and energy cannot be understated. This is why I believe power pop has been and will continue to be a pursuit for musicians of any age, particularly young ones.

Artists are inspired by the things they love, and it’s hard to think of a more enduring love affair than the one we have with the Beatles. Young musicians will invariably attempt to write songs that somehow echo their style. Most will try and fail, but even now—this very second—there’s a band in a basement or a rehearsal room somewhere writing one of those songs that will send you straight to power pop heaven.

And they’re gonna need a good drummer.

Ira Elliot has been a rock and roll drummer all of his adult life. After graduating the prestigious High School of Performing Arts, he began playing in bands in his native New York City. In 1983, he became the drummer in garage rock revivalists The Fuzztones and in 1995 joined indie rock band Nada Surf with whom he still plays. He is also a founding member of Hamburg-era Beatles band Bambi Kino.

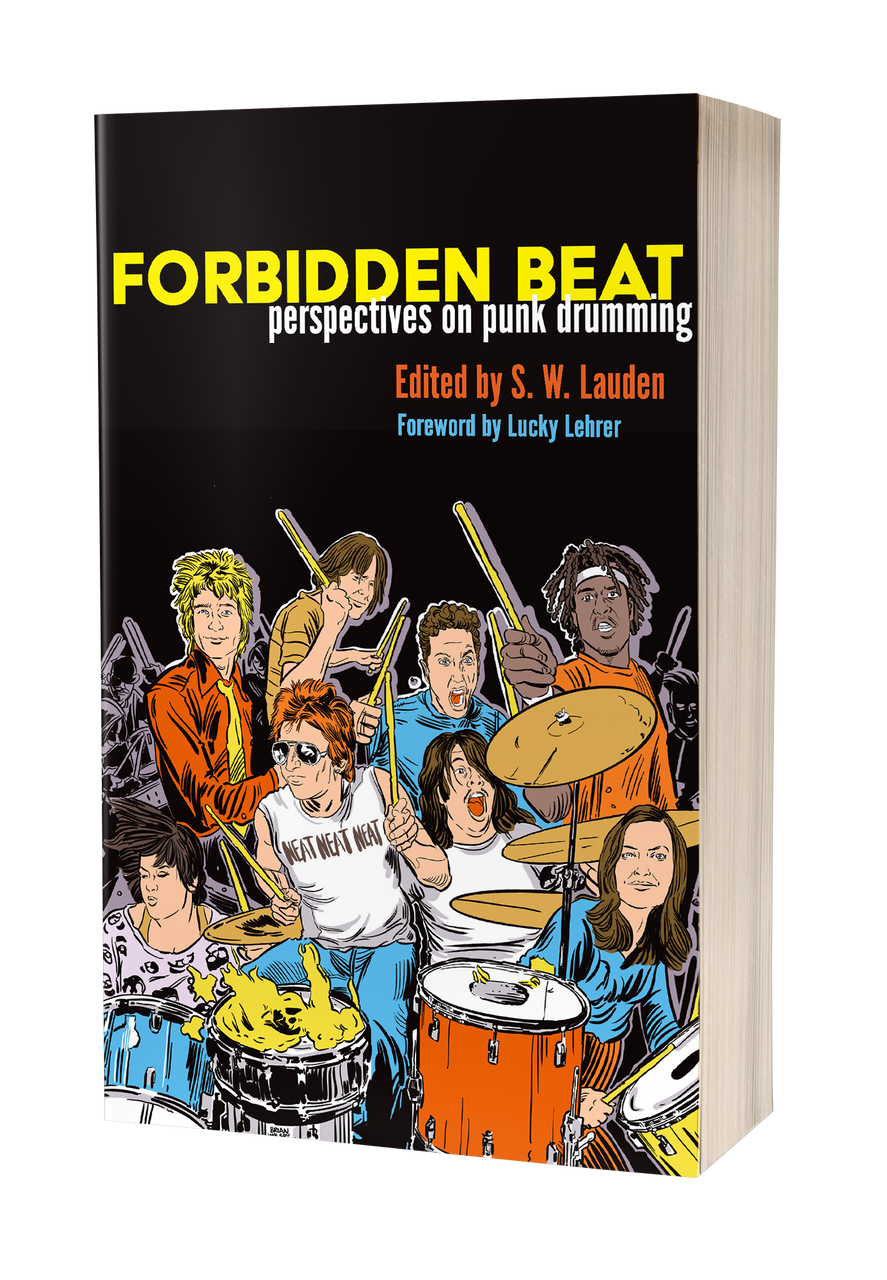

If You Love Reading About Drummers…

Whether they're self-taught bashers or technical wizards, drummers are the thrashing, crashing heart of our favorite punk bands. In Forbidden Beat: Perspective on Punk Drumming, some of today's most respected writers and musicians explore the history of punk percussion with personal essays, interviews and lists featuring their favorite players and biggest influences. From 60s garage rock and proto-punk to 70s New York and London, 80s hardcore and D-beat to 90s pop punk and beyond, Forbidden Beat is an uptempo ode to six decades of punk rock drumming.

Great piece. And while I know nothing about drumming other than what I like, one of my favorite drummers is/was Ed Breckenfeld, who played for the Insiders back in the mid-late 80s. More Roots Rock than Power Pop, but it's a fine line. I jokingly describe them as the Big Star of Midwest Pop Rock.

The quality of this video is terrible - it looks like a 15th generation tape - but it gives you an idea of his drumming.

Every day we have to get closer to an announcement of a new Nada Surf album , right?