How Do YOU Define Power Pop?

Some Timely Thoughts On The Ever-Evolving Genre

Power pop is the debate club of rock and roll.

There’s nothing that devoted and knowledgable fans of this genre love more than mixing it up about which artists, albums and songs qualify as power pop and—perhaps, more importantly—which ones definitely do not.

Approached with an open mind, it’s a fun way to celebrate the music we all love in online forums, fan pages and record store aisles. Done poorly, it can quickly become an exercise in reductive reasoning, self-importance, and purism.

Truth is, there is no definitive definition for power pop (despite what some hyper-opinionated fans would have you believe). The term was coined by Pete Townshend in 1967 to describe “Picture of Lily,” but the genre has been evolving ever since.

Even if you start with Big Star, Badfinger and Raspberries in the early ‘70s, the jump to The Nerves, Cheap Trick, Nick Lowe and The Records isn’t exactly a straight line.

There are common influences and a shared love for big hooks and harmonies, but the earlier ‘70s groups sound more classic rock than their genre mates from a few years later when pub rock, punk and new wave come into the mix.

Early ‘80s power poppers like Phil Seymour, The Plimsouls, and Marshall Crenshaw perfected the form, while late ‘80s/early ‘90s acts like Teenage Fanclub, Enuff Z’Nuff, Material Issue, The Muffs, Jellyfish and Sloan pushed the genre’s strict boundaries by adding elements of alternative, pop punk, grunge, psychedelia and hard rock—with Fountains of Wayne ultimately carrying the power pop flag into the new Millennium.

I’m making some huge leaps that skip over many other important artists and eras, but given the stylistic diversity in the handful of bands I’ve mentioned to this point it’s clear that power pop has really never been a static genre.

In many ways, that non-stop evolution has never been more pronounced than right now.

“Power pop is sometimes perceived as a genre trapped in amber—a style of music that enjoyed an initial wave of popularity in the ’70s, refined itself in the ’80s and settled into a permanent groove during the ’90s,” music journalist and author Annie Zaleski writes in her essay about The Beths for Remember The Lightning: A Guitar Pop Journal.

“This perception doesn’t make power pop artists from these decades bad, of course, or take anything away from the piles of groundbreaking albums released during this timeframe. But the dominance of this narrative can make it more difficult to see the ways power pop has grown and changed—and continues to evolve in new and unexpected ways.”

In her essay, Zaleski points to the highly-regarded New Zealand indie rockers as a prime example of how the genre is thriving in the 2020s “because it’s more inclusive and has much broader parameters than ever before.”

“Among other things, younger generations tend to have a much more generous take on which bands are considered power pop. Artists that might have been categorized as indie (or indie pop) in years past now fall under the power pop umbrella,” Zaleski writes.

James Goodson, best known as the impressive one-man band Dazy, agrees with Zaleski that definitions of power pop have shifted significantly in recent years.

In his essay “The Power Pop-Adjacent Comfort Blanket,” Goodson explores the ways in which his own brand of hooky, high-energy rock is and isn’t power pop.

“When I think of straight up power pop, I think of: Cheap Trick, Shoes, and Raspberries; lots of bands with ‘The’ in The Name; I think of a pretty healthy amount of riffs; I think of a certain lightheartedness,” Goodson writes.

“Big hooks? Crunchy guitars? A slightly holier-than-thou devotion to referring to something as ‘pop’ when you’re talking about music that isn’t really very popular? Check, check, and check.”

In the end, Goodson concludes that his own music is power pop-adjacent (much closer to alternative rock, actually), suggesting that the same might be true for many lauded ‘90s artists—including Lemonheads, Gin Blossoms, Superdrag and Sugar—who sometimes get tagged as power pop.

“In my more diabolical moments, I sometimes dare to imagine that maybe even ‘90s-prime Teenage Fanclub is more power pop-adjacent than anyone would ever admit, as there’s something so timeless and tender about their music that feels distinct from my dumb brain’s tenuous Knack (Ha!) for spotting True Power Pop™.”

If there’s one band that captures the spirit of modern power pop, I’d say it’s The Whiffs.

This four-on-the-floor Kansas City quartet writes impossibly hooky songs with a British Invasion-meets-punk approach amplified by guitar heroics worthy of ‘70s Cheap Trick, early ‘80s Replacements, and ‘90s Teenage Fanclub. It’s modern guitar pop that would be just at home at the Cavern Club in the ‘60s as it would at Jay’s Longhorn in the early ‘80s—or on a Nuggets compilation, for that matter.

What could be more power pop than that?

Well, like many modern rock and roll bands, the members of The Whiffs have a complicated relationship with the term power pop and genre labels in general.

“I’ve never really cared that much about subgenres other than when they’re used as descriptors. People tend to get dogmatic about what something is and isn’t given their personal preferences... It’s ultimately rock and roll with a good hook,” said guitarist/vocalist, Rory Cameron.

That dogmatism—often driven by purists who demand strict adherence to ‘60s pop rock ideals—has created a strange dynamic throughout power pop’s history; namely that many bands resist embracing the label because it can feel confining.

“It’s obvious why this style appeals to people that love rock and roll—hooks, interesting arrangements, tight 3-minute-or-less songs, countless nods to the timeless pop that came before,” said guitarist/vocalist, Joey Rubbish. “Power pop will forever re-emerge with different aesthetics because it’s a formula that works. The flipside is that it’s a formula that can become tiresome and boring.”

Resistance to the power pop label takes many forms, but in the end no artist from any genre gets to control how their music is perceived and classified by music-lovers.

It all boils down to perspective and personal tastes. While it’s true that some people have more-informed opinions than others based on experience and depth of knowledge, nobody gets to claim dominion over “power pop”—not even the artists the term is used to describe.

“I have a pretty classic case of Power Pop Reluctance™: loving the music and taking influence from it, but also feeling like the designation is somehow pigeonholing or limiting,” Goodson writes. “So I start splitting hairs, warping the minutiae until it suits me. ‘But I use drum machines...It’s really quite noisy...I’m more influenced by xyz punk band or xyz semi-obscure label...Yeah the songs are fun, but this is serious shit!’”

“It’s not really. It’s just music and, honestly, you’re welcome to call it whatever you want,” Goodson concludes. “But I might call it something adjacent to that.”

How do YOU define power pop? Join the conversation in the comments.

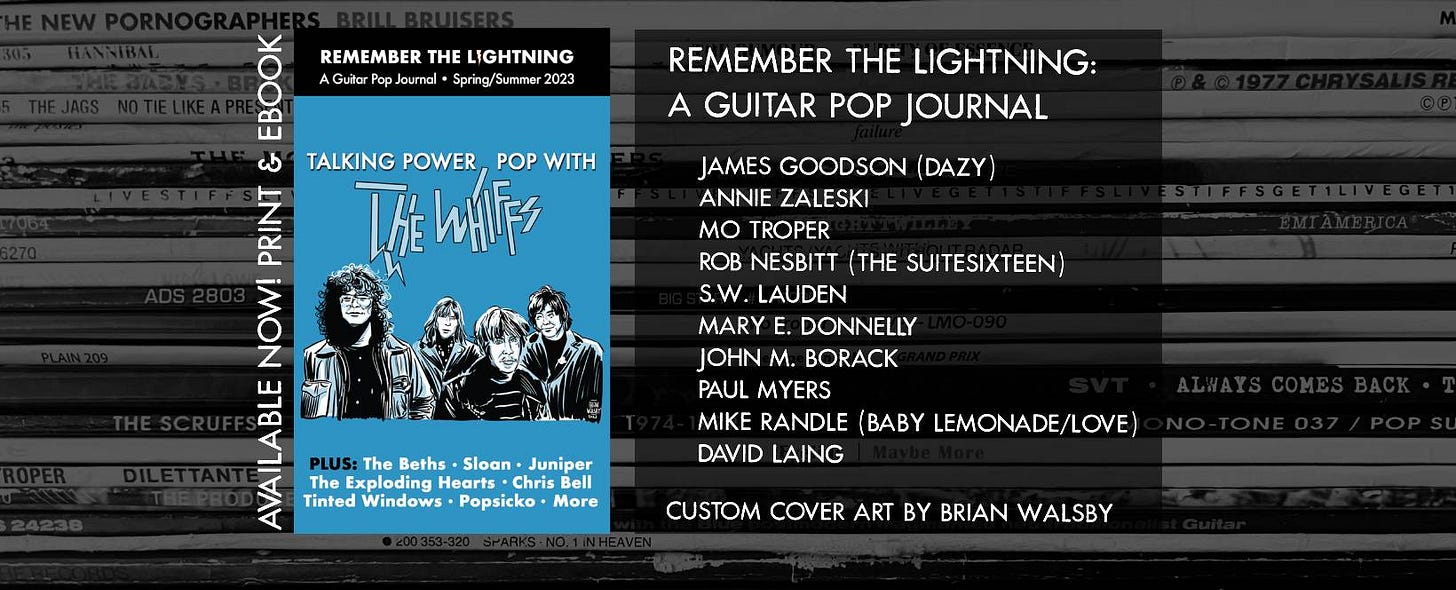

Remember The Lightning—A Guitar Pop Journal

A new semi-annual music journal featuring some of today's best music writers on modern guitar pop, and talented modern artists on the music/genres that inspire them.

I never try to think of bands as power pop; for me, it's all about the song. Big Star is usually classified as power pop, but their songs range is style from "Thirteen" to "Holocaust". About as divergent as it gets. A great song for me just happens to fit what gets labeled as power pop.

My favorite song of 2022 was from a band that is probably considered by most if you listen to their catalog as indie pop or shoegaze (and yes, there's a lot of crossover there with PP) and it's by a San Francisco band, The Umbrellas.

https://youtu.be/6jPz9qWvdrs

My definition? A ton of "oohs & aahs," soaring riffs, and hooks so sweet you fall into a sugar coma. I also agree with you that it can (should?) be defined on a song by song basis.